Edith Collier

Details

Biography

See the publication: Edith Collier, Her life and work 1885-1964

by Joanne Drayton

Biography from Te Ara (http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4c25/1) 17/02/2012

Edith Marion Collier was born on 28 March 1885 at Wanganui, the eldest of 10 children of Eliza Catherine Parkes and her husband, Henry Collier, a music shop proprietor and substantial landowner. The Colliers were a musical family and active members of St Paul's Presbyterian Church. Edith attended local primary schools and Wanganui Girls' College. In spite of the considerable domestic demands on her time and energy, she became an accomplished cellist playing chamber music in a family quartet led by her father's violin.

Around 1903, already showing artistic talent, she enrolled at the Wanganui Technical School to study art. There she worked with Ivy Copeland, Minnie Izett and, after 1909, with the English artist Dennis Seaward; she achieved high passes in the South Kensington examinations. Encouraged by the painter Herbert Babbage to seek further training overseas, Edith left New Zealand in 1912 to continue her studies in London.

She found her first few months touring and painting in Britain truly exhilarating. 'I am just in full swing now,' she wrote in a postcard to a brother; 'never had such a time in my life, working all the time.' Freed from family responsibilities, she lived a student life, rooming with other young female students at Queen Alexandra's House and attending classes at the St John's Wood Art Schools. The instruction proved conservative in its approach and Collier soon became disillusioned. Inspiration was instead provided by an Australian artist teaching in London, Margaret McPherson (later Preston), who also became a good friend.

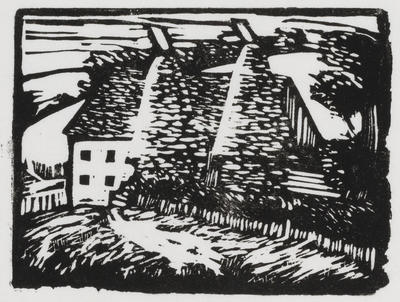

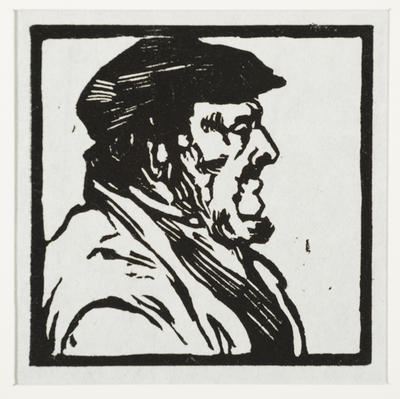

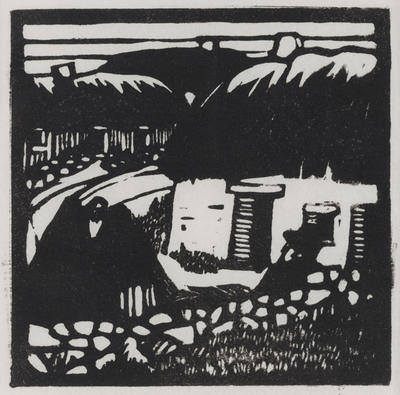

In 1914 Edith Collier spent several weeks at McPherson's summer art classes in Bonmahon (Bunmahon), County Waterford, Ireland. She attended again in 1915, staying for seven or eight months. Her portrait studies of the local peasants and her paintings, prints and sketches of their dwellings, and of the dramatic scenery at Bonmahon, remain among her finest works. The school was disbanded in the autumn of 1915, when wartime restrictions were placed on sketching along the coastline, and Edith returned to London and her new attic rooms at 5 Leinster Square.

The war initiated another round of family obligations for the artist. Her brothers and cousins were fighting in Europe, and she often provided hospitality when they were on leave, as well as organising their mail and money. This gave her a compelling reason to stay in Britain and pursue her art, in spite of pressure from her parents to return home. She hired her own life models and continued to work and travel with Margaret McPherson. While in London she exhibited mainly at women's art venues; her first positive review came from the 1917 Society of Women Artists' exhibition.

Edith Collier remained in Britain after the end of the war, and with Margaret McPherson's return to Australia she looked to other women artists for direction and tutorage. She exhibited at the Women's International Art Club show in 1920, and in the same year joined Frances Hodgkins's classes at St Ives. There she began producing the most comprehensively modern and experimental work of her career. 'I have one very bright N. Zealander, from Wanganui, Collier by name', Frances Hodgkins wrote to her mother. 'I'll make something of her I feel sure.' Convinced of Edith Collier's talent, Hodgkins could not anticipate the overwhelming obstacles her protégée would soon face.

Persuaded by her family to return home, Edith Collier left England in December 1921. In New Zealand she quickly assumed the responsibilities of the eldest unmarried daughter. Nursing and helping family members meant she had limited time for her art. Trips to Maketu Pa near Kawhia in 1927–28 resulted in some of her best New Zealand work. She exhibited with the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts in 1927 and 1928, and with The Group in 1929 and 1931, and appears to have been among those selected to represent New Zealand at the Empire Artists' Exhibition in London in 1937. In spite of this continued involvement and apparent success, her capacity to carry on painting innovatively was seriously curtailed. Savage criticism of her work on her return to New Zealand, negative responses from her own community, and the burning of the majority of her paintings of the female nude by her father left her demoralised and artistically incapacitated.

A reserved and modest woman, Edith Collier produced less and less as she got older, and by the time she died in Wanganui on 12 December 1964, some of her extended family did not know she had painted. Pointing out the irony of it all, a painter friend wrote just before the artist's death: 'It is funny how many women begin painting after families grow up while sinners like you & me Collier never touch it now altho' it was our life work in our youth!' The major public holdings of Edith Collier's work are at the Sarjeant Gallery, Wanganui, and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington

Published with the assistance of the Edith Collier Trust, Sarjeant Art Gallery and Whanganui Regional Community Polytechnic.

Edith Collier's contribution to New Zealand art as an innovator, modernist and expatriate painter placed her in a most distinguished group, but her achievements have been eclipsed by the very company she kept - such as Frances Hodgkins and Margaret Preston. This book - and the travelling exhibition it accompanies - sets the record straight.

After a thorough although conservative art education at the Technical School in Wanganui, Edith Collier left New Zealand in 1913 for St John's Wood Art School in London. She was then aged 27. Rapidly disillusioned, and feeling marginalised as an expatriate woman painter, she became more influenced by other expatriates in London, and was to enjoy greater success through exhibiting with the Society of Women Artists and Women's International Art Club - venues outside the art establishment - and became a significant Modernist painter.

Collier returned to New Zealand in 1922 as an experienced artist with innovative ideas, but as a spinster in provincial Wanganui received harsh treatment, including what Drayton describes as savage, critical assessment and negative response from her own community. In a well-known incident (on which Drayton casts a new perspective) her father burned many of her finest paintings. She died in 1964.

Dr Joanne Drayton was, at the time of writing, a tutor in Art History at Whanganui Polytechnic. She now lectures in Art History at Unitec in Auckland. For her PhD at Canterbury University she studied the life and work of Edith Collier.

PUBLICATION: August 1999

by Joanne Drayton

Biography from Te Ara (http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4c25/1) 17/02/2012

Edith Marion Collier was born on 28 March 1885 at Wanganui, the eldest of 10 children of Eliza Catherine Parkes and her husband, Henry Collier, a music shop proprietor and substantial landowner. The Colliers were a musical family and active members of St Paul's Presbyterian Church. Edith attended local primary schools and Wanganui Girls' College. In spite of the considerable domestic demands on her time and energy, she became an accomplished cellist playing chamber music in a family quartet led by her father's violin.

Around 1903, already showing artistic talent, she enrolled at the Wanganui Technical School to study art. There she worked with Ivy Copeland, Minnie Izett and, after 1909, with the English artist Dennis Seaward; she achieved high passes in the South Kensington examinations. Encouraged by the painter Herbert Babbage to seek further training overseas, Edith left New Zealand in 1912 to continue her studies in London.

She found her first few months touring and painting in Britain truly exhilarating. 'I am just in full swing now,' she wrote in a postcard to a brother; 'never had such a time in my life, working all the time.' Freed from family responsibilities, she lived a student life, rooming with other young female students at Queen Alexandra's House and attending classes at the St John's Wood Art Schools. The instruction proved conservative in its approach and Collier soon became disillusioned. Inspiration was instead provided by an Australian artist teaching in London, Margaret McPherson (later Preston), who also became a good friend.

In 1914 Edith Collier spent several weeks at McPherson's summer art classes in Bonmahon (Bunmahon), County Waterford, Ireland. She attended again in 1915, staying for seven or eight months. Her portrait studies of the local peasants and her paintings, prints and sketches of their dwellings, and of the dramatic scenery at Bonmahon, remain among her finest works. The school was disbanded in the autumn of 1915, when wartime restrictions were placed on sketching along the coastline, and Edith returned to London and her new attic rooms at 5 Leinster Square.

The war initiated another round of family obligations for the artist. Her brothers and cousins were fighting in Europe, and she often provided hospitality when they were on leave, as well as organising their mail and money. This gave her a compelling reason to stay in Britain and pursue her art, in spite of pressure from her parents to return home. She hired her own life models and continued to work and travel with Margaret McPherson. While in London she exhibited mainly at women's art venues; her first positive review came from the 1917 Society of Women Artists' exhibition.

Edith Collier remained in Britain after the end of the war, and with Margaret McPherson's return to Australia she looked to other women artists for direction and tutorage. She exhibited at the Women's International Art Club show in 1920, and in the same year joined Frances Hodgkins's classes at St Ives. There she began producing the most comprehensively modern and experimental work of her career. 'I have one very bright N. Zealander, from Wanganui, Collier by name', Frances Hodgkins wrote to her mother. 'I'll make something of her I feel sure.' Convinced of Edith Collier's talent, Hodgkins could not anticipate the overwhelming obstacles her protégée would soon face.

Persuaded by her family to return home, Edith Collier left England in December 1921. In New Zealand she quickly assumed the responsibilities of the eldest unmarried daughter. Nursing and helping family members meant she had limited time for her art. Trips to Maketu Pa near Kawhia in 1927–28 resulted in some of her best New Zealand work. She exhibited with the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts in 1927 and 1928, and with The Group in 1929 and 1931, and appears to have been among those selected to represent New Zealand at the Empire Artists' Exhibition in London in 1937. In spite of this continued involvement and apparent success, her capacity to carry on painting innovatively was seriously curtailed. Savage criticism of her work on her return to New Zealand, negative responses from her own community, and the burning of the majority of her paintings of the female nude by her father left her demoralised and artistically incapacitated.

A reserved and modest woman, Edith Collier produced less and less as she got older, and by the time she died in Wanganui on 12 December 1964, some of her extended family did not know she had painted. Pointing out the irony of it all, a painter friend wrote just before the artist's death: 'It is funny how many women begin painting after families grow up while sinners like you & me Collier never touch it now altho' it was our life work in our youth!' The major public holdings of Edith Collier's work are at the Sarjeant Gallery, Wanganui, and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington

Published with the assistance of the Edith Collier Trust, Sarjeant Art Gallery and Whanganui Regional Community Polytechnic.

Edith Collier's contribution to New Zealand art as an innovator, modernist and expatriate painter placed her in a most distinguished group, but her achievements have been eclipsed by the very company she kept - such as Frances Hodgkins and Margaret Preston. This book - and the travelling exhibition it accompanies - sets the record straight.

After a thorough although conservative art education at the Technical School in Wanganui, Edith Collier left New Zealand in 1913 for St John's Wood Art School in London. She was then aged 27. Rapidly disillusioned, and feeling marginalised as an expatriate woman painter, she became more influenced by other expatriates in London, and was to enjoy greater success through exhibiting with the Society of Women Artists and Women's International Art Club - venues outside the art establishment - and became a significant Modernist painter.

Collier returned to New Zealand in 1922 as an experienced artist with innovative ideas, but as a spinster in provincial Wanganui received harsh treatment, including what Drayton describes as savage, critical assessment and negative response from her own community. In a well-known incident (on which Drayton casts a new perspective) her father burned many of her finest paintings. She died in 1964.

Dr Joanne Drayton was, at the time of writing, a tutor in Art History at Whanganui Polytechnic. She now lectures in Art History at Unitec in Auckland. For her PhD at Canterbury University she studied the life and work of Edith Collier.

PUBLICATION: August 1999

b.1885, d.1964

Place Of Birth

Place Of Death

Nationality

Related Information